(Almost) Predictable beings in a Techno-social World

Cambridge Analytica made headlines worldwide for having played a role in the US elections and Brexit vote.1 The company was able to access personal information not only about Facebook users who had given consent, but also those who were “connected’’ to them. This scandal raised alarm about the use of personal information to show targeted advertisements to people and influence their voting decisions. However, this scandal is only one instance in a wide range of issues that plague the techno-social ecosystem. The issue is not only about data protection and privacy, but about humanity itself.

Using phones while eating, swiping down to refresh your twitter feed, retweeting and liking posts; those are just a few examples. Do you desire to pursue these activities or were you coerced to perform them? The answer is not a simple yes or no. However, the work of psychologists can help us here. Research by psychologists and behaviour economists shows that humans are “predictably irrational”2 and should be “nudged”3 towards making better decisions. Note that this line of thought goes against the belief that humans are rational agents who take into account all the available information and make decisions based on a thoughtful assessment of the cost and benefits.

Nudge theorists may be well-intentioned, but what prevents the practitioners from nudging people into actions that harm them rather than benefit them? When the purpose of nudging is to deliberately mislead users, it can also be called social engineering or psychological manipulation. Technology platforms vie for the attention of users and use various forms of social engineering to keep users on their site for as long as possible, even if such actions might harm users in a manner that they do not foresee.

At the centre of the Cambridge Analytica scandal was the sharing of personal information about users, without consent, by Facebook. Would it have been a non-issue had the users given consent? People encounter numerous legally binding contracts such as terms of conditions and privacy policies as they use many websites on the Internet. Seldom do people stop to think about the conditions of the contract before they click ‘I agree’. Not only are many of the these contracts time consuming to read, they are also filled with legalese that make it hard for many people to understand them, if they got around to read them.4 A New York Times article from 2019 claims that “only Immanuel Kant’s famously difficult “Critique of Pure Reason” registers a more challenging readability score than Facebook’s privacy policy”.5

Frischmann and Selinger argue that it is not by accident but by design that people agree to long and hard to read contracts without reading them.6 Websites display contracts such as privacy policies so that they can abide by the law. However, from the user’s point of view, these jargon filled pages are in the way of the actual purpose of their visit to the website. In fact, not even long and hard to read contracts are required to obtain consent surreptitiously. Merely having to encounter numerous notifications (even cookie consent notes with binary choices) are sufficient to tire users and nudge them into giving consent.7 Designers understand that, psychologically, users are more inclined to choose the default option to easily move from the contract notices to the actual website content and, hence, the designers often pre-select the default option that is in the business interest. Furthermore, to exploit the behaviour of people “like simple stimulus-response machines—perfectly rational, predictable and programmable”,8 websites require their users to merely click a simple ‘I agree’ button to consent to all the conditions in the contract and continue on their otherwise seamless experience of using the website.

People run on autopilot mode and click ‘I agree’ irrespective of the context, the website, information collected, etc., although the consequence of this click differs across context. This behaviour affects our lives beyond our visit to particular websites. We are told that more information is always better. But, is it? If we are unable to weigh different news sources from a friend’s opinion from a climate scientist’s view on climate change, are we necessarily better off with having access to more information? Being overloaded with information can turn us into passive, conforming, thoughtless machines. Furthermore, when we are enveloped by environments that are designed to get us addicted and feed us cheap bliss, we slowly lose our critical thinking ability and as a consequence, our ability to judge.9

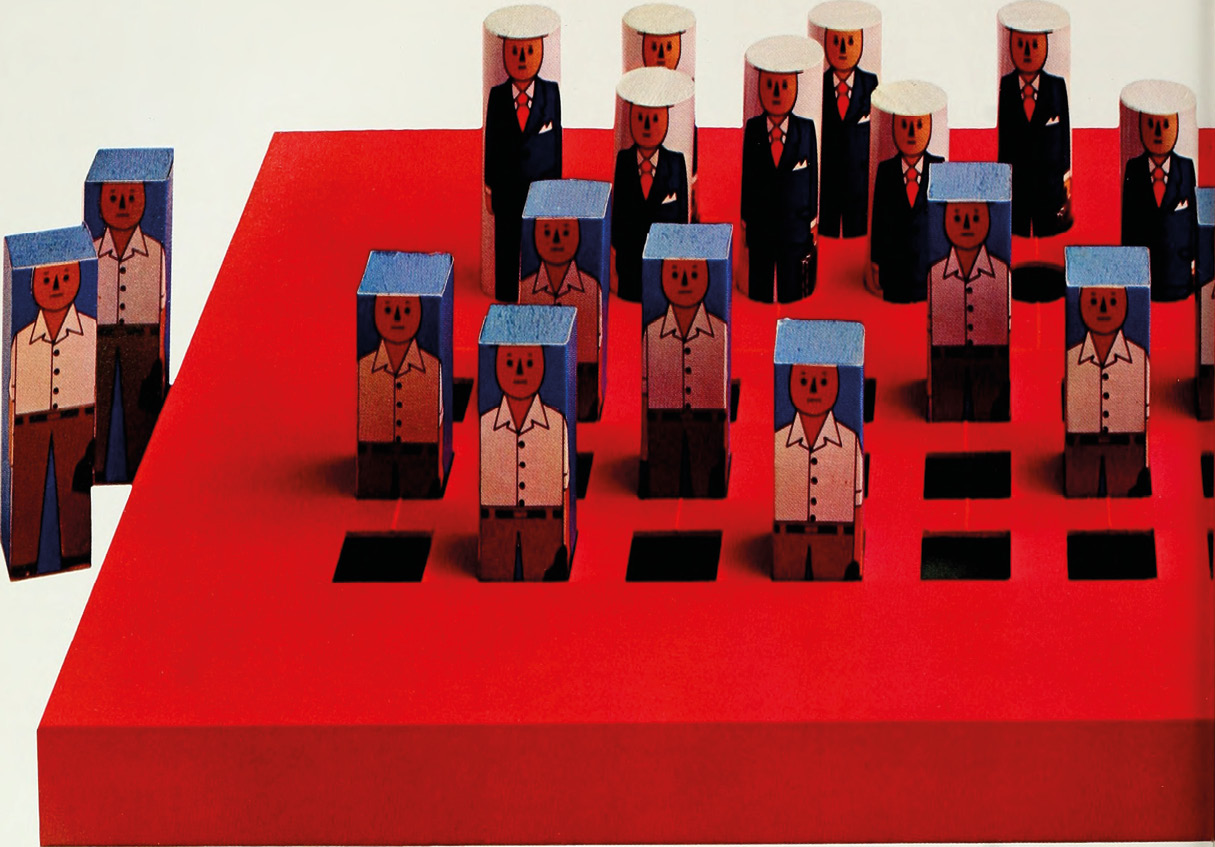

Although it might seem that large technology platforms are maliciously turning humans into predictable machines, they have designed the environments and the addictive interfaces to amass a large fortune for their CEOs, while the human and social consequences are side-effects; albeit well-known to them, as an emotional engineering experiment by Facebook shows.10 It can be seen that attention economy and “surveillance capitalism”11 play an integral role in the techno-social engineering of humans. Companies are engaged in a form of capitalism where the constant collection, storage and processing of data is normalized. There are companies that use manipulative nudging interfaces or “dark patterns”12 that give users an illusion of control while, at the same time, deceiving them into making choices which are not in their best interest but that of the companies that exploit the information collected for monetary gains.13

Anything that can be made into a data point is turned into one. Often, mobile applications collect personal information that gets passed to large platforms like Facebook. Sometimes, applications also collect information that has nothing to do with the service that the application provides. For instance, a menstruation application asked women whether they are trying to get pregnant before they could use the application,14 as this information can be sold to advertisers who place a higher price tag on the data of pregnant women. Targeted advertisers do not let go because “if a woman decides between Huggies and Pampers diapers, that‘s a valuable, long-term decision that establishes a consumption pattern”.15 Thus, large platforms do not even need users to sign up to their platform to collect and commodify information, and profit from predictable behaviour.

As convenient as it might be to blame big technology platforms for turning us into pawns in their pursuit of profit, we, the users of these platforms should take some of the responsibility. We benefit from these platforms. We want to search, connect, interact, and communicate instantly. In a certain sense, we benefit from the social value that technology platforms provide. Our individual decisions appear to be completely rational. However, we need to question whether we are benefitting as a collective.16 We have outsourced just about everything, including our thinking. Although we are not entirely predictable yet, we are on a slippery slope to become such beings. Do we stop this slide or do we continue down this path as we pursue cheap bliss that is one click away and lose out on our ability to pause, think and judge?

Footnotes

-

Cadwalladr. C (2017). The great British Brexit robbery: how our democracy was hijacked. theguardian.com ↩

-

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably irrational : the hidden forces that shape our decisions. New York, NY: Harper. ↩

-

Thaler, R. & Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge : improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. ↩

-

Such tactics have resulted in projects such as Terms of Services; Didn’t Read that aim to assist the public. https://tosdr.org/ ↩

-

Litman-Navarro, K. (2019). We Read 150 Privacy Policies. They Were an Incomprehensible Disaster. https://www.nytimes.com/inter-active/2019/06/12/opinion/facebook-google-privacy-policies.html ↩

-

Frischmann, B. M., & Selinger, E. (2016). Engineering humans with contracts. Cardozo Legal Studies Research Paper, (493) ↩

-

Utz, C., Degeling, M., Fahl, S., Schaub, F., & Holz, T. (2019, November). (Un) informed Consent: Studying GDPR Consent Notices in the Field. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (pp. 973-990). ↩

-

Frischmann, B. M., & Selinger, E. (2016). Engineering humans with contracts. Cardozo Legal Studies Research Paper, (493). ↩

-

Schüll, N. D. (2012). Addiction by design : machine gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ↩

-

Kramer, Adam D. I., Guillory, Jamie E., and Hancock, Jeffrey T. (2014). Experimental Evidence of Massive-Scale Emotional Contagion Through Social Networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(24), 8788–8790. ↩

-

Zuboff, S. (2015). Big other: surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization. Journal of Information Tech-nology, 30(1), 75-89. ↩

-

Gray, C. M., Kou, Y., Battles, B., Hoggatt, J., & Toombs, A. L. (2018, April). The dark (patterns) side of UX design. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-14). ↩

-

Council, N. C. (2018). Deceived by design, How tech compa-nies use dark patterns to discourage us from exercising our rights to privacy. Norwegian Consumer Council Report. ↩

-

Privacy International (2019). No Body’s Business But Mine: How Menstruation Apps Are Sharing Your Data. privacyinternational.org ↩

-

Petronzio, M. (2014). How One Woman Hid Her Pregnancy From Big Data. mashable.com ↩

-

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. science, 162(3859), 1243-1248. ↩